Imagine a slab of rotten rock hangs above your head as you move past underneath it, or a cliff of ice waiting to cleave you to oblivion, or the snow that you tread upon suddenly gives way to the nether recesses of a glacier. Or a miss-step, a flaky hold. Such is the peril self-imposed onto the alpinist, by their own choice. But one that imposed its own steely prospect upon me and many others like me.

The doctor's office is dull, a sterile white devoid of colours. Perhaps certificates adorn the walls, marking her own personal achievements. Noise does not intrude, or is otherwise muffled. Your seat is comfortable but boring. She looks at you with her practised bedside manners, fingers clasped, and notifies you that you have cancer, or heart failure or kidney failure. Like a sledgehammer, the ice cleaving off the face of a huge overhanging serac comes crashing down. You are flung, the world stays stationary yet you are tumbling, your life will never be the same. You did not intend to climb a mountain; the mountain had found you.

Such was how my own mountain found me. In 2019, I was told my kidneys were failing and so the writing was on the wall. To prove to myself that I wasn't actually ill, I started to climb a lot more. For what better expression of vitality was there than to climb in the high mountains? I cared not for the hanging slab of rock or the crevasse lying underneath my feet; the ice had cleaved on me long ago. I was just waiting for the hit, yet at the same time, living in denial that it would ever come.

In the late spring of 2022, I became the beggar of Alps! I waddled around the mountain town barefoot and hungry looking for a place to eat. A restaurant denied me entry as they said they were too full! With a straight face, when in fact they were half-empty. This really wasn't what I wanted to hear after the hours of pain induced by my gouty descent from the mountain. My kidneys had stopped filtering the uric acid very well, so they crystallised into sharp blades in my toe joint. Every step off the mountain was a stab of a knife through it.

Afterwards, I went again, this time, harder routes. Every time I went out to do a big day, I would be racked by cramps, whole body cramps. I remember at one hut I was sprawled out on the floor unable to even feed myself as my fingers, arms and legs were cramping. Yet at this point, it was the new normal. It's just life, something that you go through to do the things you love, the things that gave you meaning. And I did derive a lot of meaning from it.

During one of these trips we were doing a traverse on a steep snow slope with my partner. And he slipped. Now these slopes are very steep, and a slip on the snow can be fatal, especially with the 1000m vertical drop below us. Thankfully, by driving the pick of his ice axe into the snow he stopped his own fall. Given that a rope was connecting us both, it would have meant that I too, would be pulled over the drop.

We continued nonetheless. At some point, because of the unstable snow conditions, we decided to turn back. This is when the second fall happened. Here, the rope I had secured around a piece of the cliff stopped the fall, without which we would surely have shared the same fate.

What kind of meaning could one derive from such a pursuit? To learn how to operate under such perilous conditions and to think clearly, and to carry on, or to turn back. These are abilities one does not obtain through comfort, but through trial by fire. I ventured out to learn such lessons, risking a lot, and indeed, they have been invaluable.

During this time, at home in the flatlands, things were getting worse. I felt nauseous, headaches which I had never had would come and leave me fatigued, unable to move out of bed. I felt like there was a blockage, sometimes it would clear and I could leverage my strength and power which was hidden underneath. But my body was becoming very variable.

In addition to this, I noticed swelling in my ankles, I would press onto them and little dimples would form. My kidneys were failing to remove the fluid trapped in my body, I was starting to urinate less and less.

Yet still, the desire to prove to myself I wasn't ill was there. I brought my parents to the Alps to show them the mountains I loved. And during the night while they were fast asleep, I walked up Aiguille de líndex 1600m then climbed a technical ridge to the top. I had never soloed at that difficulty or in such a sustained way since then. It really was a very intense experience.

Indeed, the first pitch is something I would not want to solo again. Now this isn't the hardest solo in the world, many people solo things much harder. But, this was hard for me. Looking back however, the difficulty of the climb in comparison to my ability makes it objectively unacceptably risky. But during that day, I felt like a demigod. I had walked up a very large change in elevation, moved fast over technical terrain towards the edge of my ability, reigning in all fear or doubt, operating at such a level where failure would have catastrophic consequences. And I was back down before people even got up.

Going ahead, I took a lot of strength from this. If I did this, where literal life and limb are a single false step from ruin, then I was ready for whatever was thrown my way. And certainly a lot was thrown my way.

Shortly after my return to the Netherlands, I had a doctor's appointment. As always, we would look at my results, see if the kidney function deteriorated and that was that. There was no real way of treating it. It all felt rather useless. But this time it was different. A drug came out in America that according to all the clinical trials, would halt my disease progression. I wanted to speak to her about this. This would be an important appointment. But I had not realised truly how important it would be.

I showed up in my mountain beard, my tidily combed hair and my rolled sleeve yellow button up shirt and 3 quarter shorts. She looked at me as if I were a ghost. She said, ''I expect you to be very very ill'' and yet there I was, not ill looking at all. She told me I had kidney failure. And there, I hit the ground. The world shattered into a thousand different pieces and I cried, and she cried with me. She told me she would be my second mother through all this, which she should not have promised, only your mother is your mother.

I remember leaving the doctor's office in a mix of emotions. Stunned, sad, but also as if at the foot of Aiguille de líndex ready to climb and not fall. Thinking, right, what do I need to do to move forward. My friend, Matt Kielan, called me, out of the blue, as if by premonition such is the connection we share I guess. I told him the news, the first person whom I shared it with. Then my father and subsequently my mother, this didn't go down too well with them, I remember myself being a lot calmer, but I guess this is just the curse of being a parent. Lastly I told Monika, we met under the cherry trees outside the mechanical engineering faculty and laid there for some hours, sweet hours before the storm.

From the day I learned of my condition, to the day of my surgery where they would install a permanent, catheter into my abdomen to dialyse me was about 10 days. During these 10 days I continued to fight for life, every breath and air. Quite literally, I had recently taken up Brazilian ju jitsu, and I was hooked on it. If I was choked out I could always make the excuse of being very chronically ill, to take my opponents victory away from him! Well, I usually wasn't this unsportsmanlike, and I was still strong.

My sparring sessions were on the good days, but I did have the bad ones too. As I said before, my body was variable, it was just not regulated very well. I remember barely having the energy to eat food at our dinner table and having to rest on the sofa, shivering. The next morning, having felt better I was getting a black eye. Indeed, when I showed up at my surgery I was feeling very lethargic, as if life was drained away from me. Entering the surgery room, the surgeon had asked me where I had gotten the black eye from. To which I replied, I had been wrestling and he countered, then he'd better do a good job!

Such was my pre-dialysis life; after the surgery the wound for the catheter would need to heal for two weeks before I could be dialysed. Until then, my body would continue to collapse as it would have done, all the way until death. This is what would happen under natural conditions. And collapse it did. Throughout this process I would get more and more fatigued, my body could not produce red blood cells anymore. I got more and more gouty, uric acid was building up higher and higher in my blood, toxins were seeking a way out of skin and bone.

The psychological toll of all of this, a life upended, was by far the worst. I thought I was doing good, doing fine. In fact, the spectre of the disease stalking me for so long having come out, me having to actually face it did reduce my anxiety somewhat. Yet my inner psychological pain was materialising as real physical pain. Pain which has been the most frightening, most mind-numbing pain I have ever felt.

My penis was on fire, it sounds ridiculous even kind of funny. But the pain was frenzying. I thought multiple times to get a knife and cut it off, root and stem. Obviously this would not have helped anything. I went to the urologist, I was fearing that it would be psychological, I was begging him in my mind to say that it was actually physical and he could see things. But as he said the pain was psychological, my heart sank. So it lasted for months. In those moments without this horrendous pain, life was okay, I was content even. Such was the insanity that initial month of dialysis drove me to. Until my mind finally got used to my new normal, the limbo of dialysis.

There are some things nephrologists don't know because their patients do not tell them, and they have not experienced it themselves of course. The patients don't tell them because mainly, the topic of conversation is either their drugs or their results or the transplantation. Of course, I felt a lot of physical symptoms. My body was like a sponge with no release, water would come in and it would not leave, so I was bloated with 15l of water. There were days where I wouldn't drink anything or eat watery things, I was fatigued and nauseous. Very strange experience.

I also felt a huge mental burden constantly carrying a catheter attached to my body, a hose snaking its way around my abdomen keeping me alive, carried in an elastic band. Every breath I took I could feel it, protruding from my body. It was quite literally dysphoric, an alien appendage permanently affixed to me. I also felt inadequate at times, and guilty. I was fearful that I could not meet my social obligations, everyone expects something of their friends, family and partner. This could be as simple as spending time together, or more. Yet the disease has other plans of course.

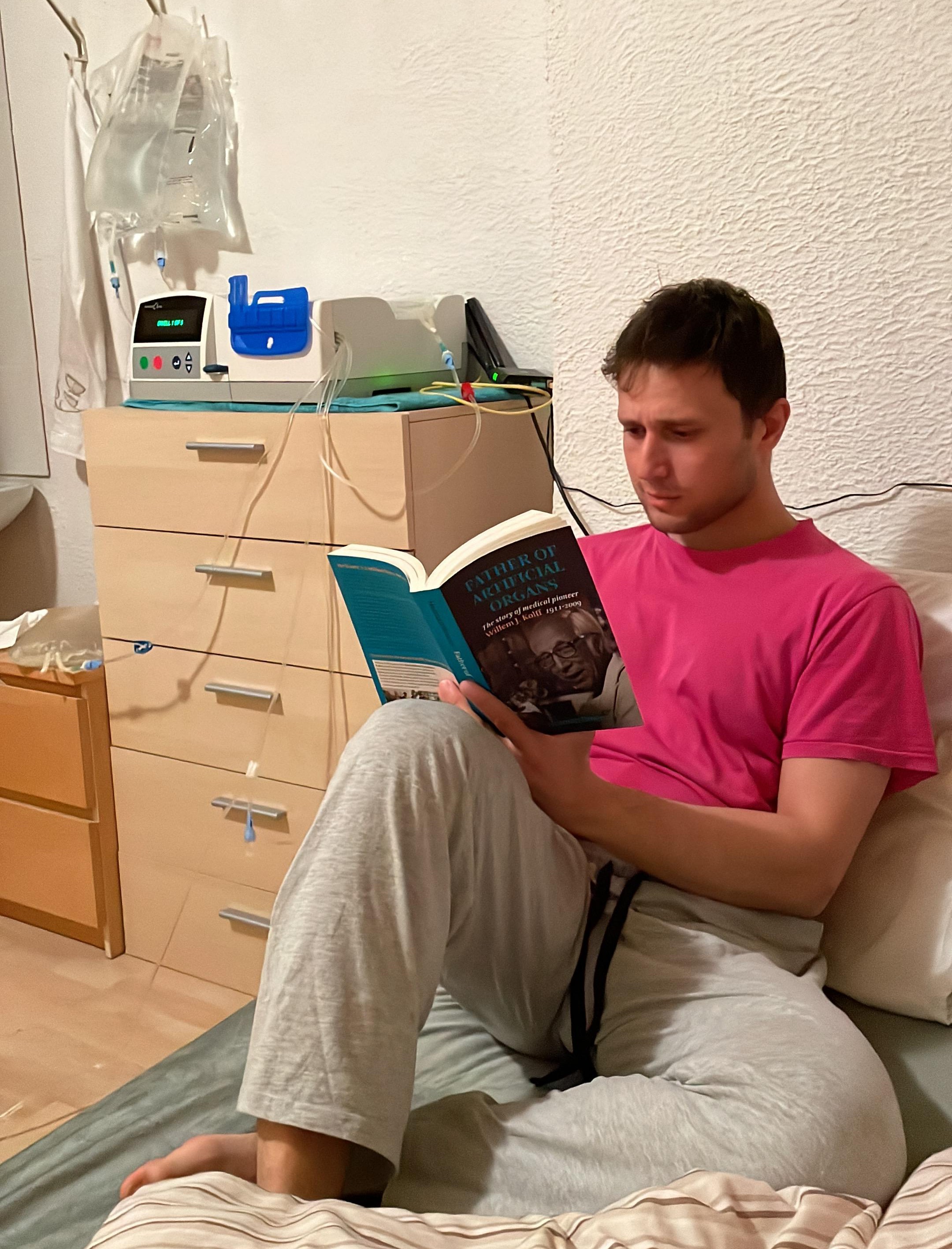

Every day I would go to work, and every night I would connect to the machine. My machine would drain 10l of fluid, in two hourly intervals the machine would remove 2L. Sometimes some would stay so I would wake up with my belly like a drum, waiting for the next drain to empty it all. I had to be plugged in every night for 8 hours. I had to receive shipments of this stuff every 2 weeks in a truck, a full pallet that was stored in a room of my house, my hospital room. The machine was at my bedside, I called ''her' Clara. I think Monika was quiet envious of her!

When the nurses were flushing my dialysis system for the first time, I and Monika had to wear a mask because of the infection risk. I looked up through the corners of my masked face to hers. I saw myself being in this position again and again over the course of my life, as my transplants failed, again and again. I owed it to her to not be in this position again, laying on my back as fluid was pumped in and drained out of me to keep me alive. No this cannot be an inevitability, I would find a solution, I need to find a solution. I would work for free if I had to, the beggar of the mountains would hence become the beggar of the flat lands.

I started ravenously reading. I believed that the final solution would be completely biological. So I read about kidney organoids, nephron sheets, iPSCs, the ureteric bud and so on. I also started contacting research groups with e-mails. I wanted a change. I could not in good conscience remain bound to my whilst I could be doing something to never need it again. I applied to LUMC for an internship, likewise to the EMC and goodness knows however many other places. From these two I received replies, which encouraged me further. In the end, I agreed with the EMC to start an internship. I was incredibly grateful for this. The grease monkey me would learn biology, it would be a long road. But perhaps at some point I would have the chance to help to create a kidney.

At the same time I was talking to the EMC, I applied to the UMCU for a position I wasn't interested in for still an important project that improves dialysis but doesn't free us from it. And I told them this, I told them I was looking for a more permanent solution. And Karin, very softly said that actually, maybe they had something for me. It would be to build an artificial kidney.

I had a real dilemma. I wanted to be made completely whole, biology would be the way to this. But the road to that is too uncertain, with a lot of research and perhaps, in the end, one cannot build a kidney without the embryological niche. But perhaps one could engineer one, first from inorganic materials and chemical coatings, a device. Then with gels, scaffolds and cells. It was a cross-road, whatever decision I made then, would determine the outcome for the rest of my life.

I made the decision as I was walking back from Monika's house to my machine, Clara. I hated sleeping apart. On this day I was feeling particularly bad, from the absence of whatever electrolyte, my legs were like jelly, I felt like a ghost walking through streets, my mind still with her. And I stopped. I could not tolerate this anymore. I would not be a researcher, I had done plenty of that. I would instead be an engineer, I had to build something, to make it so that in 10 years' time I would not be holding my child's hand with a catheter wrapping its way around my body.

So I accepted Karin's offer. Through my subsequent interactions with her and Jeroen and Fokko I realised how fortunate I was. Here were people that actually cared, their hearts were in the right place. They were not motivated by patents, greed or recognition by the academic priesthood. They were fiercely smart and massively driven. They had a problem, they saw the suffering around them every day on the ward, so they too wanted a solution. A solution, no matter how ambitious it was, no matter how impossible it seemed.

Karin generally has a timid demeanour but soon I found out that the interior holds a bold woman who has incredible drive to realise her vision. Being the mother of 2 young children, a clinician and a leading academic, is an insane load on such small shoulders, but one that she lifts like an absolute titan. She told me that I had to do whatever it took to get it done. I was hired and my starting date was the date after my transplant

The day before my surgery, I was bed-bound with high amounts of fatigue, nausea and a cracking headache. To those that know severe altitude sickness, this is broadly what it corresponds to. At the hospital, I was connected to my dialysis machine for the night. To my delight, the nurses had already set it up. The night was fitful, but when the morning came I emptied my abdomen fully for the surgeon.

My mother was taken in first. And so all was set, the surgery would happen. There would be no last minute mind changing, no ifs no buts, it would happen. I went into the surgery room, feeling dreadful.

I woke up from the surgery. Never had I experienced such a step change in my state of existence. It was as if a magic ritual was performed in the operating room and the incantation was ‘‘Anastomosis’’. The man that went in and the one that came out, were not the same. I was wheeled into my mother’s room. The nurses held out the urine bag to her like a newborn. The fluid that was trapped within me was gushing out, the blood full of toxins being cleaned. My mother was lying there, as the woman who had given me birth for the second time.

Leaving the hospital for the first proper time, the sun was shining and I felt free. I will never forget the feelings of those hot rays touching my cheeks as the car drove on to home. It was a beautiful moment.

In the days after the transplantation my mind was hooked on question. What is my kidney function? Every morning blood would be taken and the kidney function reported. And every morning I would wait with nervous anticipation in front of the computer to see them.

On the 3rd day, I could see that there was a snag, it was no longer improving but instead, decreasing. You are always told that this is a possibility, a rejection event. They had said such things are treatable, but having undergone a year on dialysis then the surgery, it doesn't stop it from being will-shattering.

Here I was, barely able to move, facing yet another biopsy. I laid there waiting to be carted back into a surgery room, to be again poked and prodded. I felt a seething sense of injustice, for yet again I was in this position. The biopsy, owing to the superficial location of my mother's kidney, was easier than my earlier ones, first of which was when I was but a boy. They indeed confirmed rejection and started giving me heavy doses of prednisone.

This to my delight did start fixing things up, yet it would still be a bumpy ride to come, with setbacks but on the whole, it was mostly down-hill from there.

Leaving the hospital for the first proper time the sun was shining and its hot rays kissed my cheeks as Vivek and Monika drove me on home. I had felt trapped, life had been sucked of all color and joy. And aside from that late moment of day that I could lay next to my Monika, it was a monochrome of existence. But now that turbid veil was blasted off revealing the beauty around.

I came home to my mother who was 'recovering' by bouncing up and down the stairs of my steep-staired Dutch house, preparing food with giddy joy. She had recovered well, only 5 days after surgery she walked 10km. For her this too had been an emotionally hard journey, her child had been suffering and she was too.

From this year I came to understand the importance of family. Without my partner I could not have endured without losing my sanity and without my mother I could not have endured without losing my health.

I wanted to return as quickly as possible to my mountains, because this would be where I would propose to Monika. For what would be a better place to propose a life together than the peak I had soloed only a year before?

I did not let her in on my plans of course, but we started training together, running and climbing. It was peculiar, cardiovascularly I felt weaker than I was during dialysis. I couldn't exert myself to the same degree. I think this was because the new kidney quite radically shifted my circulatory system, being placed in the groin area. More than that, I was taking a lot of new medications for which my body had to adjust to, not to mention recovering from the surgery itself.

My first outdoor climb was a month after the surgery after which came a trip to the UK for my sisters graduation. Me and Monika did a route on my favorite mountain here, Tryfan. Again I had soloed it in the winter before, storm conditions, this time we were together and she was carrying the pack! My fitness was improving however, I would soon be ready for the high alps.

In September, 3 months after the transplantation I was back home, an ant amongst the giants. I proposed to her on top of the Index, barely space enough to sit close to each other, let alone get on a knee. I actually opened the ring box the wrong way around and my heart skipped a beat. It would have been an expensive mistake were the ring not pressed tightly inside.

Transplantation was a life restoring, indeed, life continuing event. I could carry on as a releatively normal person. A marriage, children, perhaps an eventual guiding job in the Alps with a house in Aosta surrounded by valleys, forests, snow and ice capped peaks. To die at a ripe old age, with your grand children visiting their rugged grandparents lodge, dining on Chamoix meat. These are my fantasies. Yet life cannot be as this. My kidney has a finite life. I have talked to many fellow suffers who have had transplants that have failed upon them. Who had to 'go back to dialysis'. I have deep sympathy for them because the thought of going back, rips me asunder. No one should have to go back to that colorless, degenerative existence.

We need you to help us fight back.

The Artificial Kidney Program was kicked off by the European Union in May 2023, aiming to develop an implantable artificial kidney. However, there is a general difficulty with these large-scale initiatives: the funding often isn’t concentrated enough to unlock their full technological potential. This is a demanding challenge, and splitting just a couple of million across a big consortium—where a large portion goes to overhead and administration—can dilute momentum. Moreover, dispersing funds among multiple actors with varied motives and management structures can, at times, even hinder progress. In my view, what’s truly needed is a dedicated core team that doesn’t just coordinate remotely but works shoulder to shoulder in the same space, aligned on a single agenda.

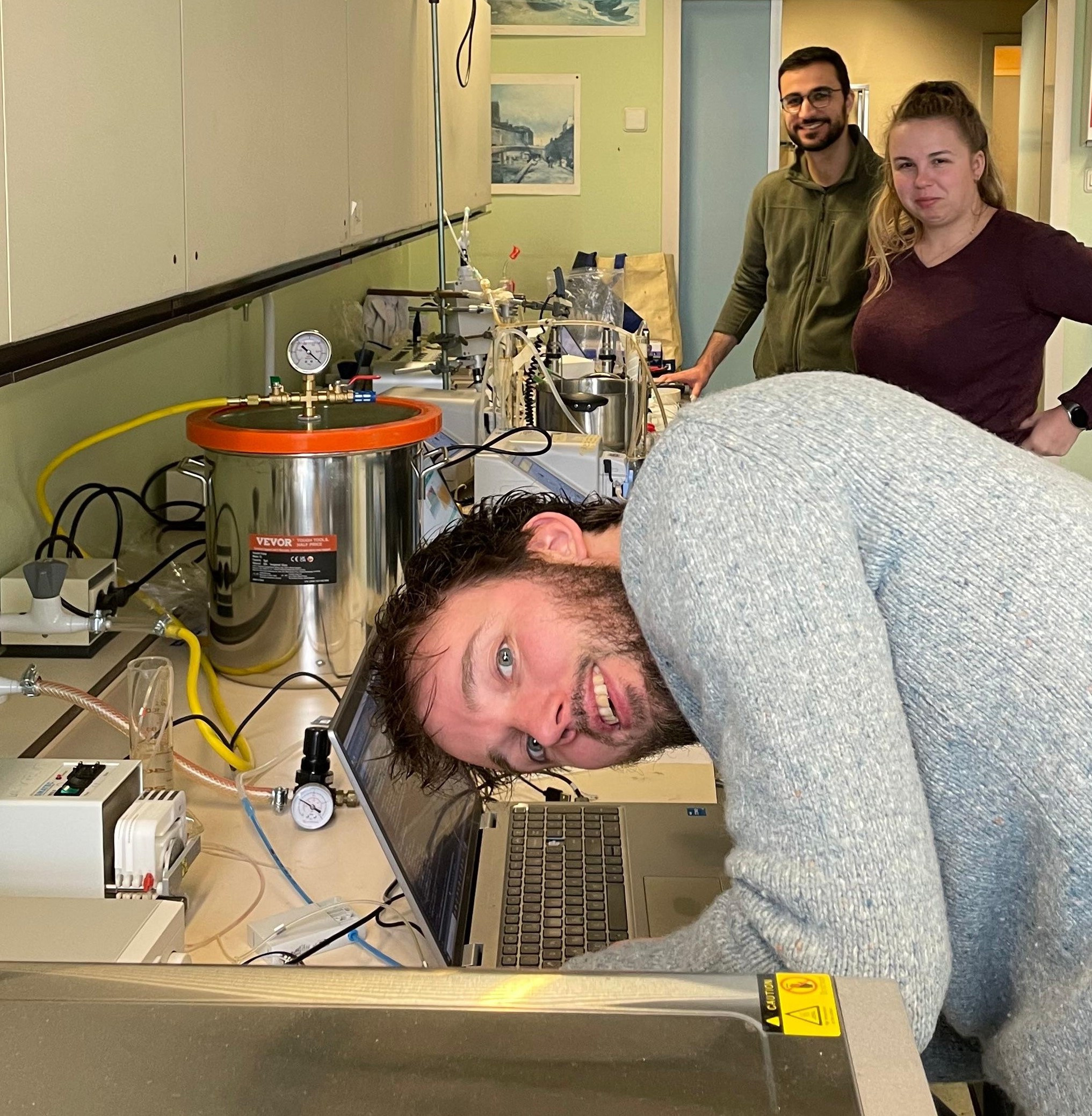

Under these circumstances, I entered the lab three weeks after my transplantation, still juggling medication adjustments. The lab, however, was practically non-existent for engineering. As a hospital mostly focused on biological research, it lacked the technical facilities needed to build an artificial kidney. What we did have was the GDL: an old, mostly disused animal lab from the 1970s, fashioned like a nuclear bunker crossed with an asylum, reinforced by thick concrete walls. Unsurprisingly, anyone who worked there tended to leave the moment they could.

Yet space is prime real estate, and the GDL was the only real space available on campus. I embraced it. Decades of clutter, dating from the 1980s to 2020, had to be cleared out. I brought in technical equipment, even orchestrating a friendly takeover of another room from the university. By February, I could start building electronics and flow cells to test membranes; by that summer, I was ready for blood testing.

I also realized the lab offered a unique advantage: being an animal lab, we could move from device design and manufacturing to bench-top and animal testing, all within the same corridor. Then, it’s just a short trip across the road to the hospital for clinical trials. Such capability would allow us to move fast. This vision was shared by Jeroen, a brilliant person and engineer whom I respect deeply. He had been living two hours away but was now moving much closer.

As conditions improved, Jeroen and I began forming the cohesive central group we’d envisioned. Soon Tadeo, Dian, and others joined, and students started coming in more frequently to contribute in their own ways. The lab kept growing, and we’ve now reached a point where we can genuinely start building momentum. We’re testing and developing chemical coatings for blood compatibility, creating 3D resin formulations, and designing a state-of-the-art hemofilter. Meanwhile, I’m working with my students on the cellular bioreactor side, and Ronald, over at the pharmacology group, has been deepening our understanding of the biology.

By the start of Climb Against Time, our aim is to have developed a hemofilter prototype. After that, we’ll need more hands and minds to help optimize it, while I shift my focus to merging Ronald’s biological insights with our engineering to create a full bioreactor and ultimately, a viable artificial kidney. The bioreactor is a huge challenge, and of course, time is always short, and there are only so many hours in the day.

In the end, I see two possible paths: either my kidney fails sometime in the future, and I return to dialysis, or our efforts work out, at which point I’d be honored to be the first person to go under the knife.